I have always been a visual person. If I need to educate myself on a new scientific concept, the first thing I search for is a schematic. However, while some scientific ideas are easy to diagram, others resist being flattened into lines, arrows, or equations. Over time, I’ve learned that the concepts that interest me most — complexity, emergence, ambiguity, and layers of meaning — often fall into the second category.

For me, translating these ideas into art form is not about illustration. It’s about further contemplating about the meaning behind these images.

This post is a reflection on how neuroscience concepts move from abstraction into a physical, tactile process, and why working this way continues to inform how I understand both science and art.

Choosing the Concept

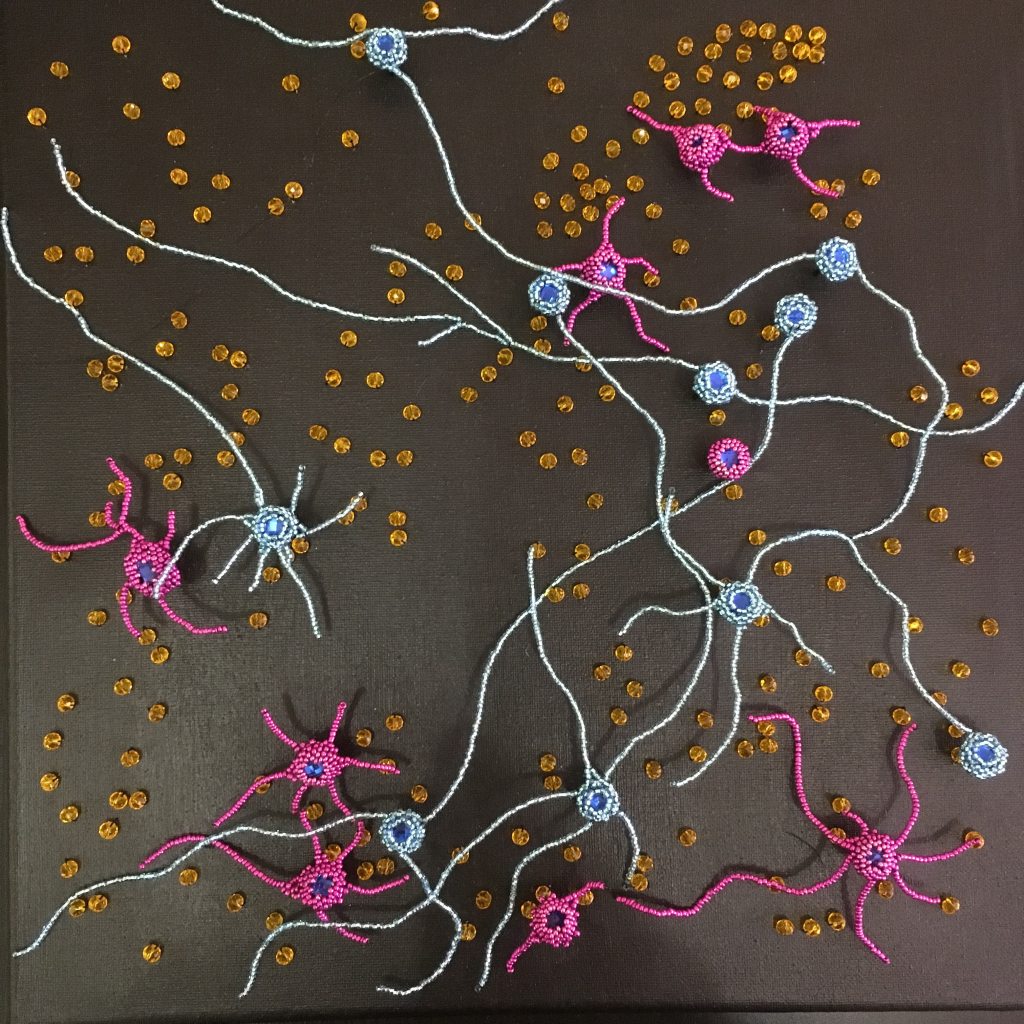

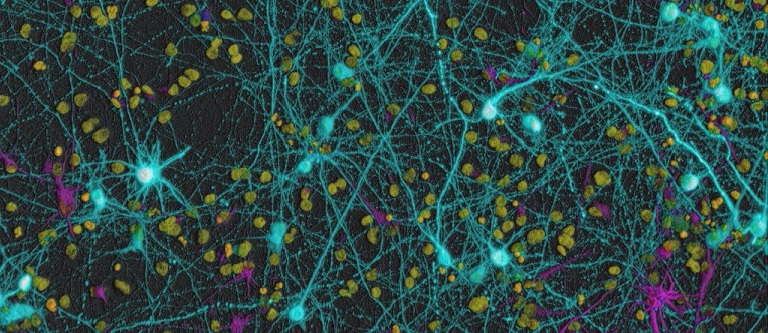

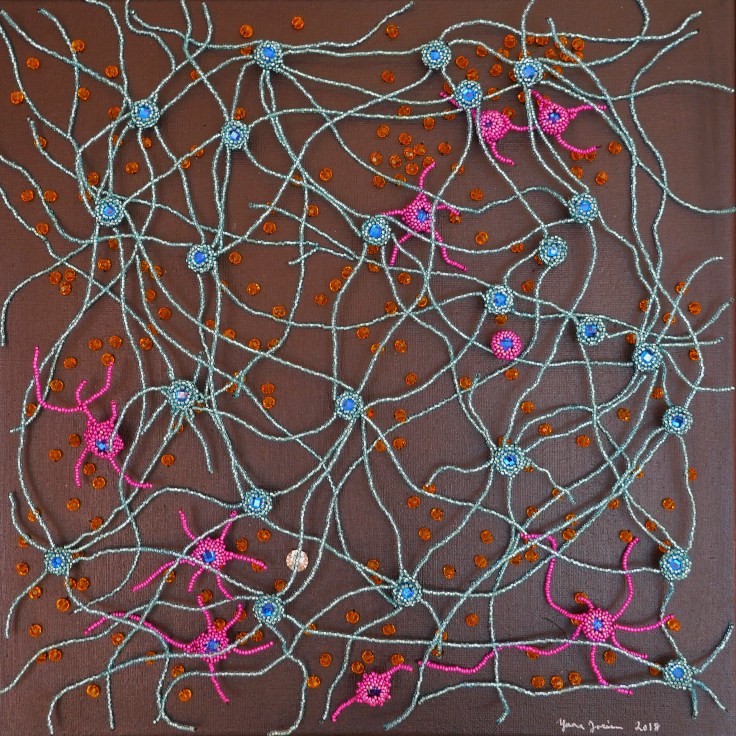

Not every neuroscience concept lends itself to physical translation. As a scientist who has spent over 20 years studying cells in a dish, I tend to gravitate toward translating flat fluorescence microscopy images into 3-dimensional structures that may do a better job at resembling what these cells look like in a living organism.

- How are they distributed rather than localized in physical space?

- What are the relationships between individual structures?

- What is the correct viewpoint that would help us better understand them?

At this stage, I start out with a detailed fluorescence microscopy image and think about how to balance scientific accuracy and educated assumptions about further layers. Technique is also very important to me and, occasionally, I choose an image based on new construction methods rather than subject.

From Abstraction to Structure

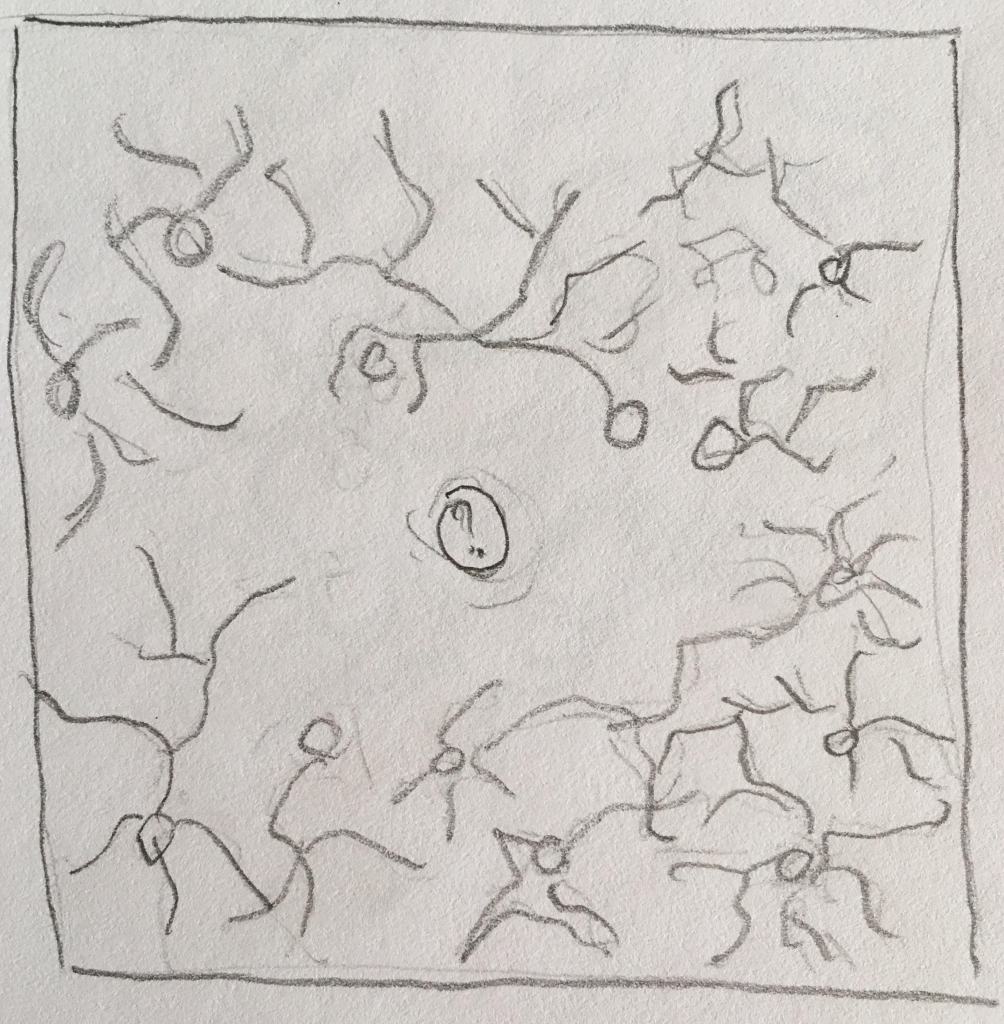

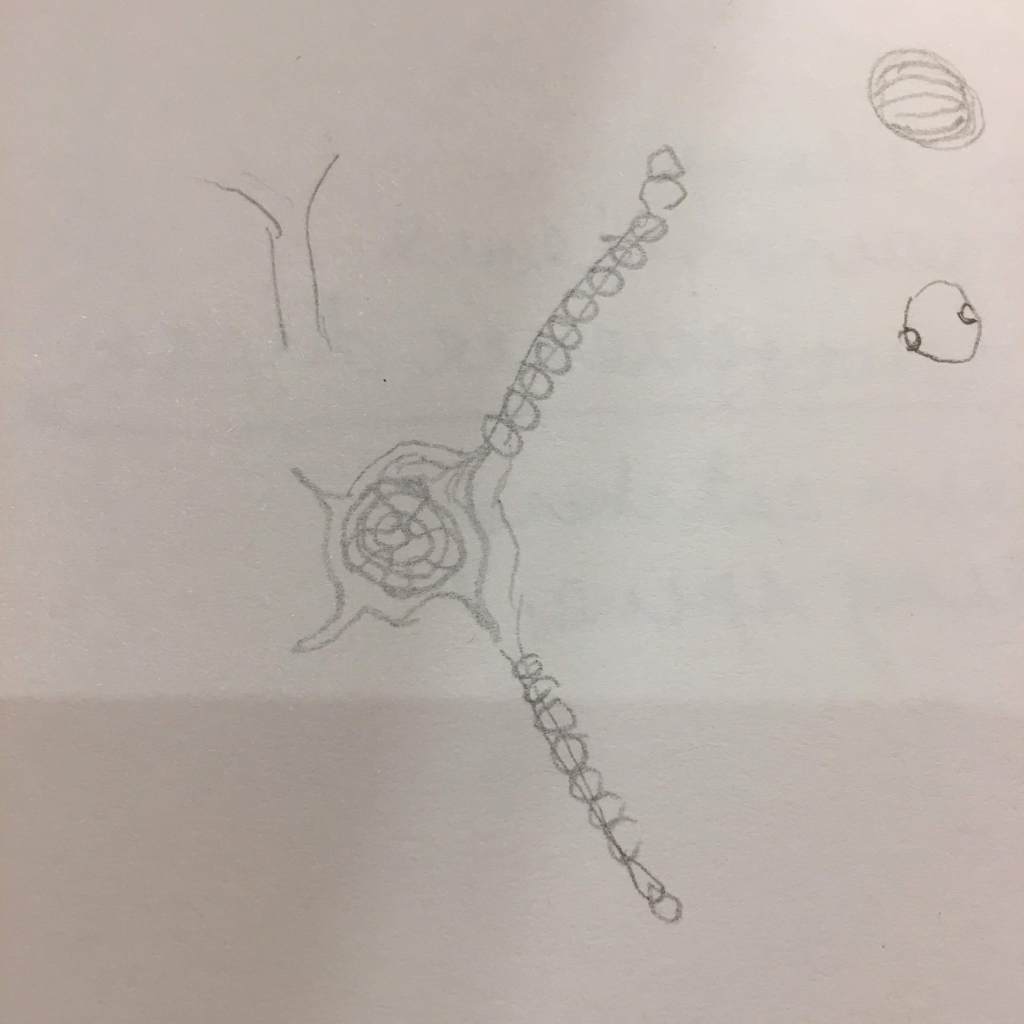

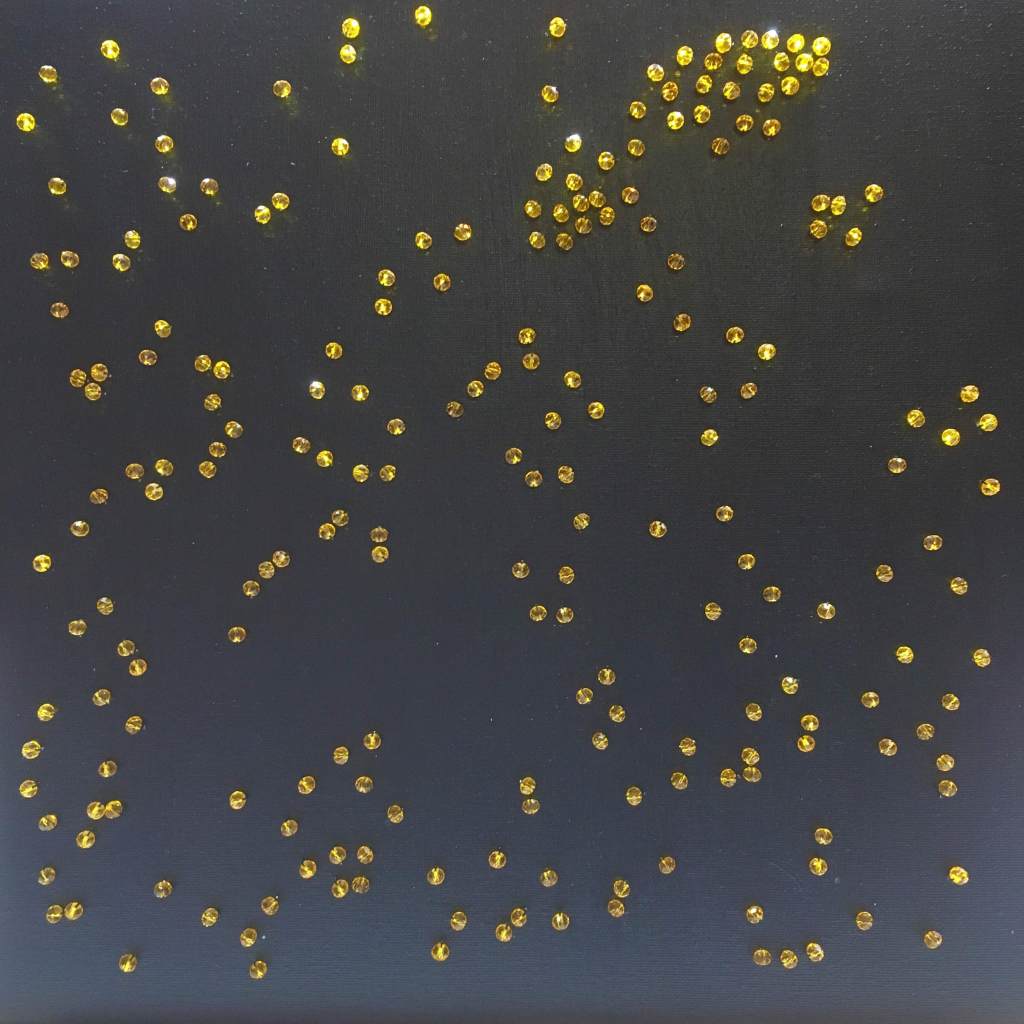

The transition from image to structure happens slowly. Early sketches are loose and provisional; they function more as placeholders than plans. In particular, I am fascinated with how different domains can be constructed in 3D space such that, at first glance, they seem fragile, yet are robust enough to withstand the test of time. This process is very important, because once I begin working with beads, most decisions become virtually irreversible.

Beadwork imposes constraints that are both technical and conceptual. Every element must support itself. Density, tension, and directionality all matter. A change in one area propagates outward, often forcing adjustments elsewhere.

This is where the work stops being speculative and becomes investigative. The process begins to answer questions I didn’t know how to articulate at the outset.

Iteration, Correction, and Uncertainty

Midway through a piece, clarity and instability often coexist. Some areas feel resolved, while others remain challenging and interdependent. These moments are rarely visible in finished photographs, but they are central to the work.

Iteration at this stage is not about refinement alone. It’s about testing relationships: How do I remain faithful to scientific structures, yet leave enough room for artistic creativity? What happens if this region becomes denser or contains larger structures? How do I make the overall image remain balanced? Which elements can change, and which must remain fixed?

Work-in-progress images capture these moments of constant negotiation with myself. Looking back at them now, I see not just the evolution of a piece, but the accumulation of decisions that led to its final form.

Deciding When a Piece Is Finished

In both science and art, knowing when to stop is often harder than knowing how to begin.

A piece is not finished when every area is resolved. It is finished when further changes no longer add meaningful information. At that point, additional intervention risks obscuring the relationships that give the work coherence, and it is time to part ways and move on to the next project.

This decision is intuitive but not arbitrary. It’s informed by time spent with the work, by repeated observation, and by an awareness of diminishing returns.

What This Process Gives Back

Working through neuroscience concepts in this way has shaped how I think more broadly. It has reinforced the value of slowness, the importance of constraints, and the idea that understanding often emerges through making rather than planning.

These pieces are artifacts of that process. They record not just an outcome, but a way of thinking — one that moves back and forth between structure and uncertainty, between intention and discovery.

Several works created through this approach are still available, and each carries its own version of this inquiry.

If you’re interested in seeing how a particular concept translated into a finished piece, you can explore the Gallery or reach out to me with questions.

Hi YanaThank you for the interesting read. You have articulated many things I think about often around translating scientific concepts into the creative realm of visual art. I have moved away from writing about art these days because I

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Darcy,

I keep receiving Google Photos memories with so many work-in-progress shots! I think they deserve to see the light of day as well. 🙂

LikeLike